Mother Nature : she can be so predictable, and its her reliable rhythms that we’ve come to depend upon and even appreciate. Organisms living and working together in ecosystems, cycling energy, recycling nutrients, cleaning the air and water, keeping things moving at the right pace so that there’s no build-up of waste. When these systems are working seamlessly and in sync, we simply notice is the beauty of nature, but when some thing throws the systems out of balance, that’s when we sit up and take notice. All too often, humans are the “thing” that threw mother nature out of balance, and it’s not until the damage is widespread do we realize the impacts of our actions. Today’s post is about just that sort of situation.

Bark beetles encompass a number of different beetle species that share similar life cycle characteristics, mainly that they all lay their eggs under the bark of different coniferous trees. As I’ll explain below, beetle activity can damage and kill trees. This often happens at a slow rate and is actually beneficial to forests: weak trees are killed, making space for healthy, young trees to grow. The “problem” occurs when bark beetle activity is happening so fast and so intensely that wide swaths of relatively healthy trees are also killed.

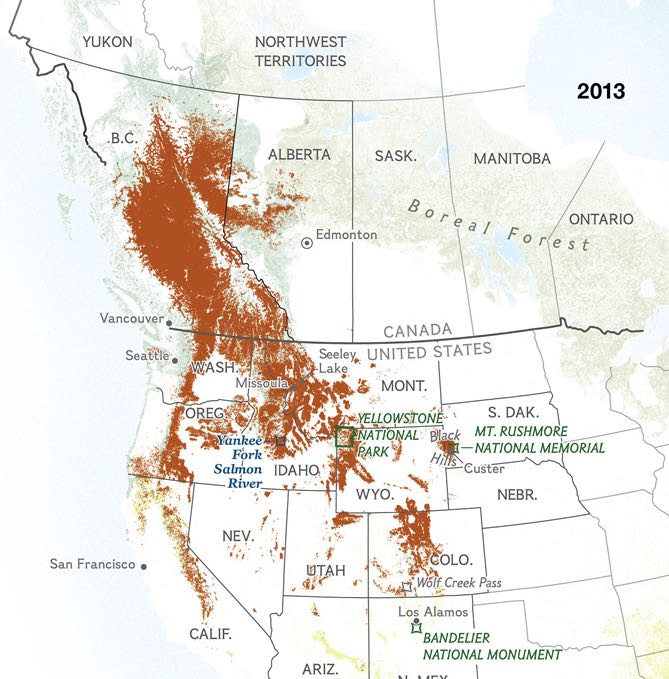

The Facts : - With 70-90% of trees killed on over 60 million acres, this outbreak is ten times larger than previous outbreaks - Forests have been attacked throughout western North America, from New Mexico to parts of Canada. - The epidemic is so large that we can not stop it. - The spread of the epidemic is slowing in some areas as the availability of trees has declined.

The beetles we’re discussing today are all native to North America. I want to stress this point : these beetles belong here and are a part of our healthy forest ecosystems, but in the past few years, their destructive activity has reached epidemic levels. What triggered this epidemic? Climate change.

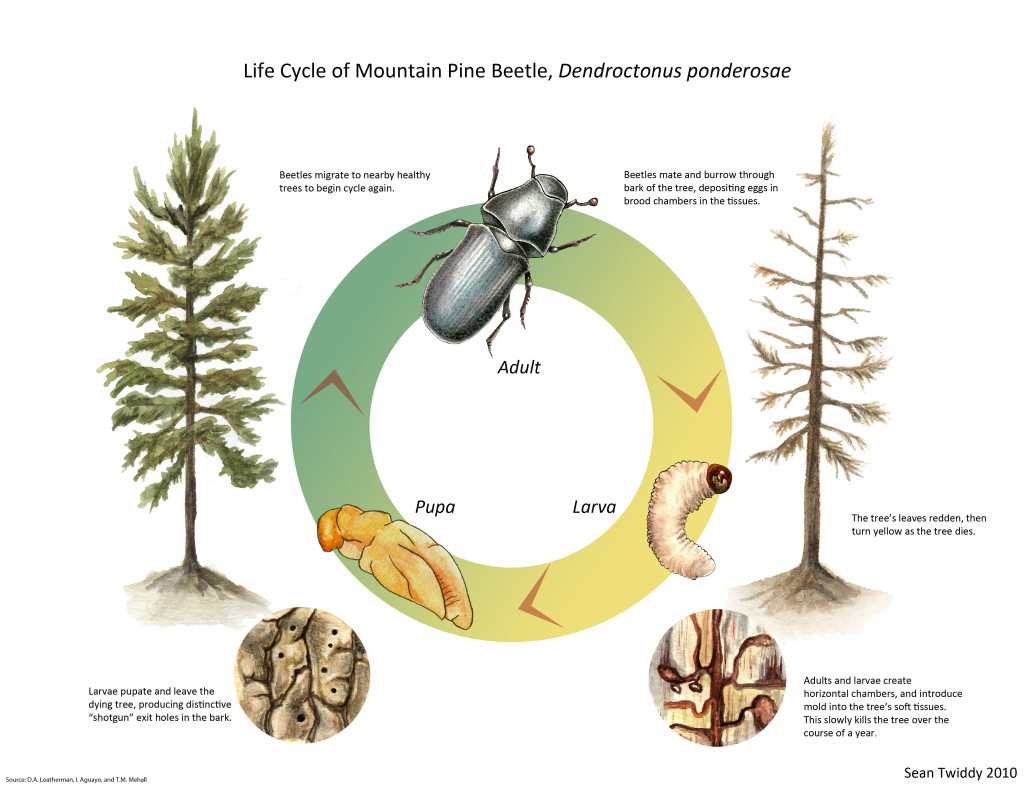

Lifecycle

As I mentioned, there are a number of different bark beetle species, and they all have a similar lifecycle. The adult beetles lay eggs under the bark of coniferous trees. When the eggs hatch, the larva then feed on the inner phloem layer of the tree before entering their pupa stage. When the pupas become adults, the beetles leave the tree to mate, and the process begins again.

Tree Death

As the female beetle attacks a tree to lay eggs, she releasees pheromones that attract other beetles. The mass attack that results from many beetles laying their eggs in one tree is what ultimately kills the tree. While detrimental, the feeding larva alone doesn’t kill the tree. When laying their eggs, the adult beetles introduce blue stain fungus.

The fungus blocks the flow of resin, water, and nutrients within the tree, and this is the final blow that kills the tree. It’s obvious that limiting the flow of water and nutrients within the tree is damaging. But what’s the story with resin? Resins are thick and sticky liquids produced by many plants and used as a defense mechanism. When an insect or other herbivore attacks a tree, the sticky resins often act as a deterrent, stopping their activity, and in the case of insects or other pathogens, the flow of resin can sometimes push the foreign body from the tree. By slowing the flow of resin directly around the eggs, the fungus allows the beetles to develop relatively unhindered by the tree’s natural defenses.

The image below shows the total area impacted by the current epidemic.

Environmental Impacts

When trees die slowly in a forest, the impact is minor : there’s a small hole in the canopy, more sun reaches the forest floor, and there’s a chance for sun-loving plants to grow in the ensuing years before the canopy hole is filled by either nearby trees or the growth of a young sprout. When a whole stand of trees dies, the impacts are much more noticeable.

Without the live trees, there are no pinecones, which serve as a food source for many animals. In particular we’ve noticed the stress on grizzly bears in Yellowstone, which rely upon the pinecones for food. Without it, the grizzlies are getting into more trouble as they roam lower, tourist-filled areas of the park.

The water cycle is intimately tied to tree cover. When the dead trees lose their needles and the canopy opens up, more snow reaches the forest floor in the winter. Without snow resting on the branches, less sublimates into the atmosphere. The snow melts earlier because the bare branches allow more sunlight through. The dead trees do not use the water, so less water is taken up and transpired back into the atmosphere. Between the greater snowpack on the forest floor, less sublimation from the upper canopy, and lower water demand by the trees, there is more available water in the immediate area.

What’s Causing the Epidemic

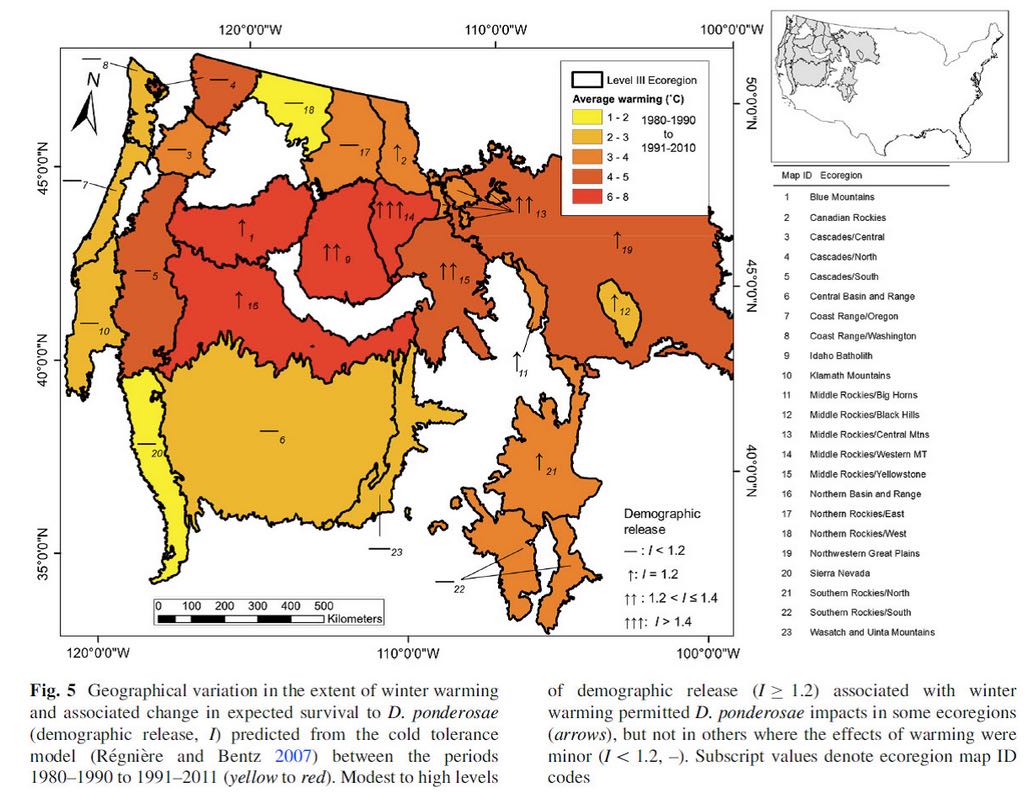

There are two climate-related issues that are thought to cause the current epidemic.

The first are the relatively warm winters experienced in the Rocky Mountains over the past decade. Sustained cold winter temperatures kills some of the beetle larva, keeping the beetle’s population in check. During the winter months, the beetle larva produce antifreeze compounds that help them survive cold temperatures, so not only do the temperatures have to get unbelievably cold (we’re talking negative 20-30F), these temps have to be sustained for close to a week to be effective. Although, if we get a cold snap earlier in winter (around October or November), then the beetles are not fully prepared for winter and a cold snap can kill off a good portion of the larva.

The second climate-related issue is the large-scale droughts hitting the western US. When water supplies are limited, trees produce less resin, further limiting its effectiveness in deterring the beetles.

Is There an Increased Fire Risk?

With large swaths of dead/dying/dry trees left standing in place, logically, you might expect the wood to fuel wildfires; not something that we want to see, especially in combination with the current drought conditions. Fortunately, there has been little data supporting this idea.

Instead, recent observations have shown just the opposite. What seems to be happening is that the needles are falling from the trees and decomposing. Without the dry needles to act as kindling, there is no elevated risk that the area will catch fire. It’s as if the beetles are thinning the forest, and this results in years of fire suppression in the infested areas.

Value of the Timber

A bark beetle infestation does not deteriorate the quality of the timber for about a decade. If harvested, the wood can still be used for building material. Some segments of wood will be stained blue where the tree was infested by the fungus, but designers have found a way to turn even this wood into a valuable product.

As you’ll see in the next section, one of the primary methods of fighting the infestation has been removing infested trees and/or thinning the forest in vulnerable areas. Since 2001, there were 55 different bills introduced into congress that each included the goal of increasing timber harvests to fight the epidemic. This paper provides a detailed account of many of the key proposals in a number of these bills.

This is where the epidemic becomes a bit political. Many permits for harvesting the timber on federal land are given to private companies, allowing them to profit on the heels of this devastating epidemic. Of course, many affected areas are too remote for harvesting to be profitable. All the while, there isn’t quite enough data to show that the harvests are effectively fighting the epidemic. Particularly, as you’ll see below, when we are starting to observe that some trees may be more genetically fit to withstand the outbreak, but our harvesting methods do not take into account the genetic makeup of the individual trees within a stand.

What’s the Solution?

When it comes to Mother Nature, sometimes the best solution is to let her alone. Did you ever hear about how we introduced Cane Toads to Australia to control a beetle? Bad idea. All joking aside, it seems like letting nature run her course may be the solution to the bark beetles, but I’ll come back to the reason why below.

There’s been a push to put resources into fighting the most recent epidemic. Why? As I mentioned above, there is little to no additional fire risk from the stands of dead trees. Rather, people what something done mainly for cosmetic reasons : the stands of dead trees look bad. People living in the infested areas are frustrated to see their beautiful mountain landscapes turn brown, and this does have an economic impact for these communities: housing prices have declined, maintenance costs increase as dead trees fall on infrastructure, and tourism dollars decline with a reduction in recreation in the affected areas.

There are a number of different management strategies used to fight the epidemic:

- pheremone baiting : as mentioned above, when a female beetle lays eggs in a tree, she releases a pheremone that attracts other beetles. We can do the same thing as a method of controlling where the beetles congregate. These baited trees can then be removed or destroyed, provided a more targeted kill of a large number of beetles.

- pesticide application : there are a number of pesticides that have proved effective, but they have to be applied to specific trees, and (of course) there is always some level of risk to other organisms in the area.

- tree removal : this category encompasses a number of different methods. In some areas, trees are being removed at the first sign of infestation in order to (hopefully) limit the beetles’ population expansion. In other areas, huge swaths of trees are being thinned in the hopes that the beetles can’t travel as easily or quickly between trees that are spread out. Tree “removal” may occur in one of two ways, either through controlled burns, or through timber harvests.

While the pesticide application has been shown to be the most effective method available for saving specific trees, it is not viable over a large region, and unfortunately, data coming in is beginning to show that perhaps our tree removal efforts are also not as effective as we once believed.

"even after millions of dollars and massive efforts, suppression…has never effectively been achieved, and, at best, the rate of mortality of trees was reduced only marginally." Six, Biber, & Long 2014

As I mentioned above, perhaps the solution to this current epidemic is to just leave it alone. What?! Most of the funding to fight the current epidemic has focused on management practices that involved removing some combination dead, infected, and healthy trees. Unfortunately, along the way, there has not been much documentation of the success or failure of these strategies, and more often than not, the trees are harvested while the beetle populations continue to grow. Scientists pulling together documentation of government funding and forest service efforts to quell the outbreak have found that “even after millions of dollars and massive efforts, suppression…has never effectively been achieved, and, at best, the rate of mortality of trees was reduced only marginally.”

But not all is lost. Some scientists have observed that there are stands of trees that remain standing and healthy in the face of a beetle infestation. It appears that these trees are genetically different are able to withstand the beetle attacks. If this is the case, then it suggests that we should re-think our management strategies. Rather than harvesting trees in the effected areas based upon size, we should harvest based upon genetics. Allow foresters to only remove the trees that do not have a genetic defense against the beetles.

Natural System out of Sync

Well, how’s that for a depressing post? Really, we don’t mean to be a bummer, but as we see the world changing around us, we want to understand these changes and share them with you.

I want to conclude this post by reminding you of a few key things : everything that we discussed is part of the native pine forest ecosystems in Western North America. The current epidemic is larger than any observed in the past, and that’s because the whole system is out of sync due to climate change-induced warmer winters and drought conditions. That means, the fossil fuels used to run our cars and power our lights are helping the beetle populations grown and the pines die at unprecedented rates. Unfortunately, that is depressing.

Images : epidemic map, winter warming map, bad beetle case, beetle life cycle. Images of dead trees taken by us while on trips along US 70 in Colorado.

this was so interesting to read, I never really thought about the genetics of a tree in being able to resist pests (fungus, bugs, whatev). good points, great post!

Thanks! Yeah, I think a lot of people are surprised by the genetic resistance! And now I think they’re in the phase of trying to figure out what’s different about the coding in those trees that’s making them resistant. Is it that they put out a chemical that’s more potent that deters the beetles? What’s really exciting is the idea that this could help us to improve our management practices and work *with* the trees.

This was so interesting to read. Hopefully, I am about to do my PhD research on this topic. After reading this I am really excited to work on them. Thank you for such a great article.

Prachi, We agree, the ecology of these forests is so interesting, and we love learning about how climate change is throwing these systems out of balance. The bark beetles are a great example of a climate-induced problem. Good luck with your future research!