Every season we like to pick one ingredient and focus on a variety of ways to use it both inside the kitchen and out. You may see the ingredient pop up in drinks, savory and sweet dishes, and cosmetic potions.

When you saw this post title, did you have a gut reaction? Are you excited for all things vanilla? Or are you thinking “ugg, how plain”? In the past I’ve definitely thought of vanilla as a plane-jane flavor and would skip it over something more exciting, but lately I’ve come to appreciate vanilla’s warm and calming scent and flavor.

We’re looking forward to a season of vanilla projects, from the simple vanilla sugar sweetening our morning coffee to experimenting with vanilla-scented homemade perfumes and air fresheners. What do you say? Are you game to play along? Any favorite uses for vanilla beans?

History

Vanilla is a seed pod produced by orchids in the genus Vanilla , that is native to Mexico and Central America. Aztecs were cultivating the plants long before Europeans arrived in the Western Hemisphere, but it wasn’t long before Spanish explorers introduced vanilla to Europe in the mid 1500s.

Although the fruit was highly prized throughout the world, unique pollination requirements caused Mexico to remain the primary producer of vanilla for the next 300 years. It wasn’t until the mid 1800s that techniques to artificially pollinate the orchids were discovered, and soon afterwards, production of vanilla outside of Mexico flourished. By the late 1800s, nearly 80% of vanilla production occurred in tropical regions outside of Mexico.

Today most vanilla comes from Madagascar and the surrounding regions, with Mexico supplying just a fraction of total supply. As you’ll read in the next section, growing vanilla is highly labor-intensive, making it the most expensive spice in the world after saffron. In the past, vanilla prices have experienced wild swings as a result of tropical cyclones wiping out crops and cartels limiting supplies. It is estimated that today 95% of “vanilla” products are artificially flavored, keeping demand for the bean down.

Biology

There are three subspecies of vanilla grown around the world today, and all originated from central America. Vanilla planifolia has the highest vanillin content and is the most popular species, with most of its supply coming from Madagascar today. Vanilla pompona and V. tahitensis are the two other varieties, and they’re grown everywhere from their native Mexico to the West Indies.

These particular orchids grow like a vine, creeping their way up trees or poles towards the sun. The flowers grown near the tip of the vine, so when grown in plantations for harvesting, the plant is periodically folded downwards to keep the flowers and fruit within reach of the farmers. This proximity is important both for harvesting the pods and for pollinating the flowers.

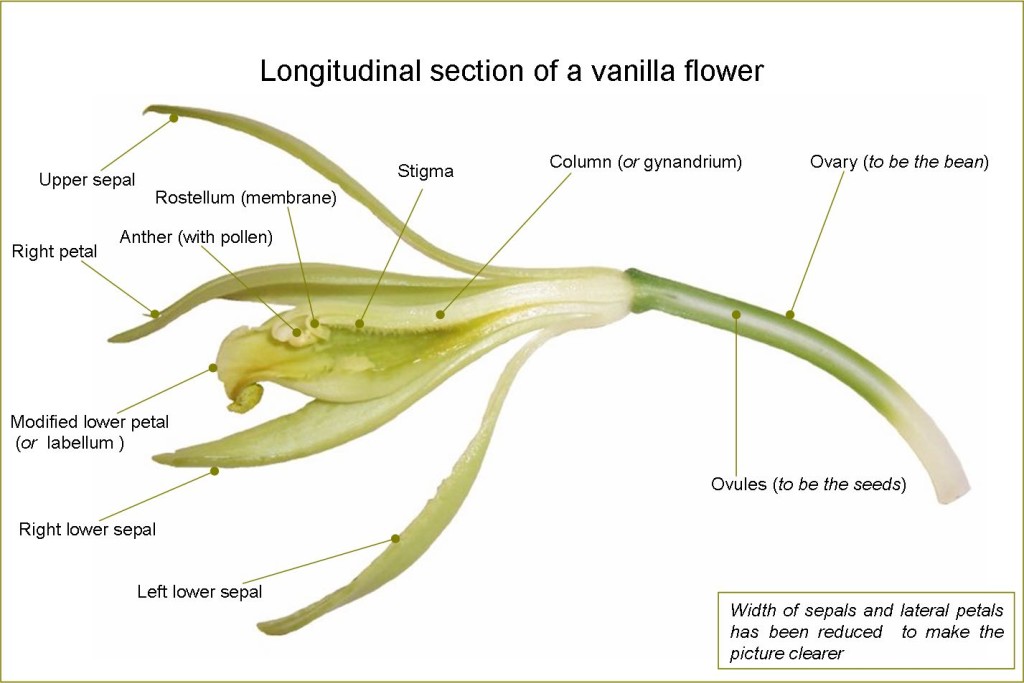

Flowers of the Vanilla orchids are hermaphroditic, containing both the male and female organs required to pollinate and produce a fruit, BUT the organs are separated by a membrane so as to eliminate any chances of self-pollination. Stingless bees of the genus Melipona are the only insects that naturally pollinate vanilla flowers, and these bees are found only in Mexico. The bees land on open flowers, work their way under the membrane separating the pollen-covered anther and the female stigma, and pollenate the flower. A few hours later the flowers close, and within days, the seedpod begins to grow.

This flower-insect relationship was not understood for 300 years, thus thwarting any efforts to grow vanilla outside of Mexico. Once it was discovered by botanist Charles Morren, he quickly began working on methods for hand-pollinating the flowers. The pollination technique was then perfected by a 12-year-old slave Edmund Albius, and his method is still used today.

Like many other orchids, the seedpods will not germinate without the presence of mycorrhizal fungi that provide an energy source to the seeds as they begin to grow. As a result, most plantations use cuttings to increase the size of their crop.

It takes about 6 months for the fertilized flower to produce a ripe seedpod. Near the end of ripening, the beans must be checked daily and then harvested by hand. After the beans are picked, they must be cured, which is a multi-step process of “killing, sweating, drying, and conditioning” the fruit. This process stops the fruit from further growth, brings out the vanilla flavor, and inhibits any mold growth. The beans are then graded based upon length, appearance, and moisture content, but these traits do not necessarily correspond to flavor!

Vanilla Varieties

Admittedly, I’ve purchased vanilla beans many times and have been confounded by the varieties, while never once did a take the time to figure out the difference between Madagascar and Tahitian or Mexican and West Indian. Well, the mystery has been solved, my friend. On the other hand, I’ve never once wondered where my artificial vanilla flavoring comes from… and now that I know, I just threw up in my mouth.

Real Deal

- Bourbon, Madagascar, and Mexican vanilla are all cultivars of V. planifolia. Mexican is grown in Mexico (duh). Bourbon and Madagascar vanillas are grown in the islands of the Indian Ocean.

- Vanilla pompona* is grown in Central and South America and the West Indies and is sold as West Indian Vanilla.

- Vanilla tahitensis* is grown in French Polynesia and sold as Tahitian Vanilla.

- Ugandan and other varieties, I’ve seen beans for sale from other regions, and I think they are also growing the V. planifolia variety.

*Remember that V. pompona and V. tahitensis have notably less vanillin than V. planifolia.

Artificial Vanillas

- Lignin is the origin for most synthetically produced vanillin. Lignin is a polymer found in wood, and so a lot of artificial vanilla is produced as a byproduct of the pulp used for paper production.

- Castoreum is a yellowish secretion from the castor sacs of mature beavers. You guessed it, the castor sacs are found down in their nether regions, somewhere between their pelvis and tail. In the US, castoreum has been approved by the FDA as a food additive (think “natural flavoring”), and it’s used to provide vanilla flavoring.

And on that note, we’re so excited for a season of vanilla projects. We never thought we’d bring beavers into this discussion.

Images : labelled flower, plantation, beans, beaver